We’ve all heard that Europe is rapidly “graying”. The combination of fewer children and longer lives means that our population is skewing old.

Of course there is nothing inherently wrong with being old. But with our society as it’s currently set up, we may run into problems. For example, our current pension systems with the young working to provide for the old will become increasingly difficult to sustain.

But — more importantly — aging is strongly associated with ill health. Some of this association is probably inevitable given the planned obsolescence inherent in our biology. But we also know that our modern lifestyles — with our poor diets, stress, lack of sleep, etc. — continually add to our risks as we age.

Spending on old age across Europe is already 25% of GDP [1]. Much of that spending goes toward general and long-term health care. With an increasingly old population in increasingly ill health these costs will become unsustainable.

So what should we do?

Well, we could cross our fingers and hope that medicine continues to produce miracles. But many of the conditions encouraged by our modern lifestyles — obesity, cognitive decline, etc. — are so complex that a purely medical solution is hard to even imagine, let alone realize. What we need are other low-cost interventions that serve to sustain physical and mental health throughout old age, while also promoting subjective wellbeing.

Healthy aging in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Sounds too good to be true, right? Not necessarily.

I recently had the opportunity to travel to Bosnia and Herzegovina to visit some of their Healthy Aging Centres (HACs) together with Prof Tara Keck (UCL Dept of Neuroscience, Physiology and Pharmacology). The centres act as hubs for older people to gather together each day to socialize and undertake various activities ranging from performance and creative arts through physical fitness and computer classes. The idea is that by providing a space for building a community, the centres help their users avoid the isolation and loneliness that often trigger a downward spiral in physical and mental health.

We were hosted by two of the people involved in the centres: Željko Blagojević from the UN Population Fund and Sejdefa Bašić Ćatić from the Partnership for Public Health. We will be working as part of a group together with the UN and local organizations to assess and quantify the benefits of the centres for their users. Our goal is to establish an evidence base to support the further development of new centres in the region and beyond.

There are currently 7 centres spread across the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska. Our first stop was Sarajevo, where we visited several centres in different municipalities. We got to experience a typical day-in-the-life of the centres and our first impressions were overwhelmingly positive. We saw some fantastic art (some of which is now hanging on my wall, thanks!), enjoyed the results of a cooking class, struggled through exercises and got humiliated by the local ping pong champs — and that was just within the first hour.

We next visited the centre in Modriča. Luckily for us, the centre was celebrating its fourth birthday and we were able to attend the party. (To their credit, the people of Bosnia and Herzegovina do not seem to need much of an excuse to throw a party. Had we visited on a different day I suspect we might still have encountered a party.) There were speeches from volunteer coordinators, local politicians and centre users (some of which were quite touching), followed by demonstrations and performances from the centre’s different creative groups and, finally, a feast. (You can read an account of the event in the local language here). The party gave us a great opportunity to hear firsthand from users how the centre provides opportunities for activity and community that would otherwise be impossible.

Our last stop was Banja Luka where we met with the team that is overseeing the development of new centres there. We discussed their plans for the coming year and identified a good opportunity to begin our research in collaboration with students from the local university who will be undertaking practical training later this year.

After visiting, it’s obvious that the Healthy Aging Centres are a great idea. You don’t need to be a scientist to see how the strong communities that flourish in the centres are of great benefit to the health and wellbeing of the users. And with running costs of only a few euros per user per month it’s hard to imagine a healthy aging intervention that is better value.

But replicating the formula that has worked so well in Bosnia and Hezegovina may not be trivial. The success of each centre, at least in the initial period following its opening, seems to rely on the dedication and talent of the coordinators to get things going. Once the centres are well established, they can become self-sustaining with much of the work done by the users themselves. But it may not always be easy to get to that point.

There is also always the challenge of finding suitable premises. The experience of the coordinators in Bosnia and Hezegovina thus far suggests that the success of the centres depends on the availability of a dedicated, permanent space that is available every day exclusively for the centre users. It’s not hard to understand why: a space that is comfortable, reliable and, eventually, familiar, is critical for creating a strong sense of community.

Healthy hearing for healthy aging

My main role in the project will be to advise on aspects related to hearing and communication. Since the benefits of the centres arise from their role as social hubs, it’s critical that they provide an environment with good listening conditions for easy communication. Even those who are young with normal hearing often struggle to communicate in large gatherings. For older people, most of whom have hearing loss, these difficulties can be even more pronounced.

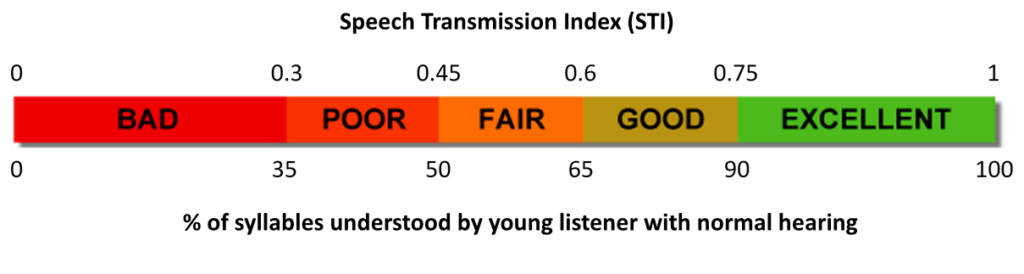

I plan to test the listening conditions in the centres by measuring the Speech Transmission Index (STI). The process is simple and requires only a speaker and a microphone. The speaker is setup to play a known speech (or speech-like) test signal from a position where one person’s head might be. The microphone is setup to record the test signal where another person’s head might be (about a meter away). After a few minutes, the microphone recording can be analyzed and compared to the original test signal that came from the speaker.

If the recording is exactly the same as the test signal — as it would be in a perfectly quiet room with no echoes — then the transmission is perfect and the STI is 1. If the recording is completely different from the test signal — as it would be in a very loud room with a lot of echoes — then the STI is 0.

In practice, the result is usually somewhere in between depending on the size and design of the room and the number of people and other sound sources present. In a small quiet room, the STI might be something like 0.8, whereas in a busy pub it might be more like 0.2. Extensive testing has been done to determine how the STI in a room corresponds to the fraction of syllables that would understood by actual human listeners who were having a conversation in that room:

But it is important to remember that these numbers are for young listeners with normal hearing. For older listeners with hearing impairment, the fraction of syllables understood for a given STI may be much lower.

The current centres vary in their layout. Some of the smaller centres consist of just one or two communal spaces, while the larger centres have both large gathering rooms and small breakout rooms. Because the small breakout rooms are isolated from the other rooms and hold relatively few people, they are likely to provide excellent listening conditions.

The large gathering rooms in the centres are inviting, bright spaces that play an important role in creating a sense of community. But providing good listening conditions in large gathering rooms is not easy. There are some steps that can be taken to dampen echoes, like installing soft furniture or curtains (UK Action on Hearing Loss has a useful guide). But since acoustics are not the only concern, there has to be a balance between providing good listening conditions and retaining other important aspects of the design.

Part of my work on the project will also be to learn more about the hearing status of the centre users. Based on their age, statistics would suggest that the majority of the users have significant hearing loss, but I observed very few hearing aids during my visit. While hearing aids won’t provide much benefit during large, noisy gatherings, they will likely make it easier to communicate during smaller group activities and are almost certainly better than nothing.

If, in fact, there is a high degree of hearing aid underuse, it is likely due at least in part to the stigma associated with hearing loss. Perhaps the communities created by the centres will provide opportunities to change attitudes toward hearing loss and make users less reluctant to seek assistance. By improving listening conditions and increasing hearing aid use, it may be possible to make the centres even more beneficial than they already are.

References

- The 2018 Ageing Report: Economic and Budgetary Projections for the EU Member States (2016-2070). European Commission – European Commission